Question: Please tell me about yourself. Where do you live? What dogs did you have and what dogs do you have now?

- My name is Adil Kozhahmetov. I was born in the USSR – the city of Alma-Ata of the KazSSR, to be exact, currently known as Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan – and have lived here my entire life. Since my childhood years and into adulthood, I kept various dogs including ordinary mongrels. As far as the breeds, we kept an Eastern European Shepherd, a Barak (a dog breed completely extinct at this point), a couple of Tobets and a certain number of Central Asian Shepherds (CAS), whom I used to breed when I took interest in dog breeding and cynology.

Question: When was the first time you saw a Tobet?

- It was sometime in the late 1970s or early ‘80s when I was a school student.

Question: What were your life occupations?

- Like most people of my era, I tried a little bit of everything, but mostly focused on PE and sports. For a while, I also developed an interest in cynology and dog breeding as pertaining to Central Asian Shepherd (CAS) breeding. This interest is long past me now, though.

Question: Why did you specifically pick the Tobet for studying, and not the Tazy?

- Tobet and Tazy are both Kazakh national dog breeds. Though I wouldn’t use the word “studying”, myself – I simply took an interest and collected bits of data where I could. I never kept a Tazy dog because I was never fond of hunting and took little interest in hounds in general. Although I did observe Tazy dogs as a child and heard all kinds of stories and legends about this breed. As for the Tobets, I took an interest in them because they managed to impress me quite a lot.

As I tried to collect information about this breed, I would often talk with the elderly, some of them born in the late 19th century, I’d read various books, collect photos with my friends, and so on. In the end, my friend A.V. Malyshevich [M1] and me published several articles on this topic. Looking back from the height of my years and a somewhat corrected perspective, I am not entirely satisfied with the quality of my work and would have altered certain aspects if I were to revisit it today.

Question: How do you feel about modern CAS breeders using your drafts of the Tobet breed standard to promote their own dogs, who they also refer to as Tobets based on your description of the breed?

- Let’s put it like this. Some breeders have used excerpts from articles where my friend and me provided a figurative description of the Tobet breed – not a standard, mind you. Second, no one has ever referenced us in doing so. Third, we described the breed for people to use this information, so if they do use it, more power to them. The only thing nagging me is that sometimes, excerpts from our works end up used in a wrong context, distorting the essence of what we tried to convey.

A little while ago, I enlisted the help of my like-minded friends to finalize the Tobet breed standard. It was then adopted by a state organization attempting to restore the breed. Our main difficulty was in the fact that the workgroup assigned to this mission largely consisted of incompetent people far removed from understanding not just the Tobet breed, but its related CAS breed as well. Furthermore, the workgroup demanded that we compose a standard in line with the requirements of the International Cynology Federation (Fédération Cynologique Internationale, FCI). I spoke out against the idea of composing such a standard or registering it in the FCI, arguing that the breed was de-facto extinct. I suggested – and even developed for a while – an extended description of the Tobet breed along with a manual for those dog breeders who would like to dedicate themselves to reviving this breed for our country’s internal use. However, there was no reasoning with the government officials, and I ultimately had to compose the standard adjusting it to their understanding of the problem. Making matters worse, some of the workgroup members actively sabotaged the standard by stubbornly insisting on using a dumbed-down CAS breed definition. Their proposed standard would be expanded to include subpar Central Asian Shepherds, which is to say, mongrels. Had we allowed it to happen, our breed restoration mission would have failed automatically, because such subpar dogs are already present in abundance both on the expanses of Kazakhstan and in Eurasia as a whole. Me and my colleagues ended up fighting for over two years to defend our stance on the standard.

Not too long ago, I sketched up a justification for the need to conduct certain tests on city-bred dogs and came up with some regulations for this process.

The tests I proposed are different from the dog trials we are used to, which are essentially just dogfights and result in shepherd dog breeds mutating into fighting dog breeds.

In our suggested test routine, we focused not only on testing for fighting abilities in wolfhounds – granted, those are essential, too – but also on determining pronounced social behavior tendencies. These are crucial if your goal is a viable canine society living freely by shepherd’s side.

The Justification also states the need to introduce the most successful individuals into their natural environment on livestock farms, where these dogs should undergo further selection. It goes on to mention the need for city-dwelling dog breeders to interact with on-farm breeders to exchange experience and breeding material for further selection work.

Regrettably, one must face the fact that the Tobet breed, as such, is currently extinct. Enthusiasts keep visiting remote livestock-keeping regions of the republic, sometimes going as far as the adjacent regions of the bordering republics, as they search for aboriginal dogs more or less fit for selection. They chance upon such dogs from time to time, but more often than not, these prove to be old and sick individuals that are difficult to get any kind of offspring from.

The way I personally see it, reanimating the breed in its original form is hardly possible anymore. Should all pieces fall into place and the enthusiast breeders do their long, painstaking work well enough, they just might recreate a breed closely resembling the original Tobet.

Complicating matters is the fact that people lack knowledge in certain important aspects. There are people with a solid understanding of cynology, but no knowledge of the breed. On the flip side, there are people whose understanding of the breed is decent but whose cynological competence is non-existent. Actually, this is why I insisted on composing an expanded standardized description of the breed complete with annotations and illustrations. It would convey an idea of the breed along with the necessary cynological knowledge. Rather than targeting fighting pit judges, this description would target actual breeders, enabling them to figure out the dog they are trying to recreate and decide on the selection steps they need to perform without any third-party testers involved. Flipping through a thin booklet to learn about a specific dog breed and gain understanding of it is both easier and more productive than studying whole tomes on cynology and then taking your dogs to be examined by third parties.

With this out of the way, we may now proceed to discussing what links the Tobet-type dog with the modern CAS breeds and whether they can be considered subtypes of the same breed. Let’s start by clarifying what the CAS breed is.

As I searched for more information on the Tobet, people told me about the ways in which nomadic livestock keepers employed dogs in a relatively recent past. This insight shed light on the whole CAS diversity situation. On the one hand, you could encounter markedly different CAS types within the same geographical region. On the other hand, you could encounter extremely similar, basically same CAS types in different regions. This state of things is descriptive of the entire Middle Asia, or, to use the more modern term, Central Asia, including Kazakhstan. In one and the same region, you may find CAS dogs with different head shapes, fur structure and length, head shapes, and so on. At the same time, while quite rare, Tobet-type dogs had nonetheless been encountered throughout the entire region until recently. In exceptionally rare cases, Tobet-like dogs are still encountered to this day, mostly in remote places where modernity has yet to spread and people cling to their old traditions. For example, you might see them in remote corners of Afghanistan, or somewhere like that.

What’s the reason for such a mosaic-like distribution?

As we know, the ways in which nomadic livestock keepers used their dogs called for selective breeding of specific types – namely, hunting dogs and shepherd dogs. By hunting dogs, we mostly understand greyhounds, although other, currently extinct breeds used to be employed in the not-so-distant past. Shepherd dogs include wolfhounds and shepherds. The hunting dogs and the wolfhounds were considered purebred and consequently treated as such. Hunting greyhounds enjoyed particular reverence. No such reverence was spared for the shepherds, although they were also valued for their guarding and shepherding abilities. Both wolfhounds and shepherds were important for this type of work. So, where did their shepherds come from and why did the nomads not treat them with great care? The reason is, their wolfhounds and hunting greyhounds were the ones that provided the breeding material for their shepherds. The nomads would often cross a Tobet-type wolfhound with a greyhound. The first-generation offspring would often prove great for hunting, mainly wolves. The Kazakh would call these dogs “duregei[M2] ”. They would often grow up to a considerable height, move faster than the wolfhounds and considerably stronger than the greyhounds. It needs to be pointed out that both wolfhounds and greyhounds came with their own natural color variations. The greyhounds were less varied and tended to be lighter-hued than the wolfhounds. By crossing two dog breeds with different natural colorations, they got extremely varied offspring colors, especially from the second generation onwards. This is how spotted piebald, jet black, white, tiger and other color varieties appeared, mixing with the natural ones. The duregei who were unfit for hunting were automatically assigned shepherding duty, as did their descendants from the next generations. In fact, they were the ones that ultimately formed the breed we’ve come to know as the Central Asian Shepherd. These dogs gave birth to nicknames like Alabai, Alapar, Koishi, Goyunchi, and so on. They were abundant and not particularly cared for, in contrast to the purebred dogs, which were scarce. With the advent of sedentary lifestyle, modern agriculture, industrialization, firearms, predator culling etc., wolfhounds have gradually lost their function in the life of the livestock farmer. They began to dissolve in the ever-growing population of shepherds. This state of things was further aggravated by populations being separated from one another as people gave up their nomadic lifestyle. Not to say that larger dogs were often culled from the population for various reasons. Dog populations getting separated from each other often resulted in degeneration from frequent inbreeding. People no longer considering the breed as valuable, no longer appreciating its function and lacking the understanding of imported breeds, compounded by a continued inbreeding of the aboriginal dogs, led to further crossbreeding, and so on, and so forth. It’s also worth pointing out the work of Soviet cynologists like Mazover and others, who, lacking an understanding of the breed, failed to restore it and instead set a new selection trend by using the remaining wolfhounds to enlarge shepherd dogs. Until recently, dog breeders would happily use these so-called “old breed” dogs to improve their Central Asian Shepherds instead of focusing on these rare and vanishing dogs as a worthy breed of its own. At the end of the day, this combination of factors led to the regression of the Tobet-type Asian wolfhound: the breed dissolved into shepherds.

So, how should we regard the Tobet dog in relation to the CAS? Figuratively speaking, it would be correct to consider the former as a kind of “superbreed” to the latter. All the various CAS types out there are on a gradient of breed traits between the wolfhounds of the past and the hunting dogs, as simple as that. The modern CAS dogs are essentially duregei. For nearly 100 years now, breeders have been trying to enlarge them and morph what is originally a shepherd breed into a fighting breed.

Why did they use the Tobet-type wolfhounds to enhance shepherd dogs instead of trying to breed them as a standalone breed? Because the process was labor-intensive, I suppose. Such dogs were rare, and collecting a sufficient amount of breeding material would prove a challenge. Furthermore, these wolfhounds tended to have a less striking and appealing exterior compared to the aesthetic and pretty CAS. Sulking, big-headed, emotionless, scruffy, with darker-hued fur and usually of average height, the Tobets were likely perceived as a remnant of a mammoth era and were not as easy on the eye as the colorful, short-haired, trim-looking CAS dogs. Moreover, the way I understand it, Tobets, being very intelligent, unemotional canines with vividly defined social behavior, weren’t a very nice fit for a fighting dog breed at all. Finding themselves outside of their home territory, their area of responsibilities, their society, these dogs needed a hefty reason to engage in a serious fight with another dog. Reason like food, or a bitch in heat, or something like that. Failing that, there’s no expecting bloody drama from a dog like this. When forced, such a dog would try to limit its involvement and avoid dealing serious damage to the opponent. Such fights would end up looking lackluster, not thrilling enough, you get the idea. These dogs would only show extreme violence to intruders on their own home turf; they needed a valid reason to do the same on foreign territory.

Perhaps this factor, along with the others I listed above, contributed to the lack of interest in breeding these dogs as a whole separate breed. Basically, other objective reasons aside, people themselves accelerated the regression of the Tobet wolfhound breed and its dissolution in the sea of Central Asian Shepherds. This is why there’s no Tobet in Kazakhstan, no Kopek in Turkmenistan, no Tobet in Kyrgyzstan, etc., etc.

When in Kazakhstan, I and my friend A.V. Malashevich tried to leverage the media to get the public interested in restoring the Tobet breed. I think it was back in the late 1990s or early 2000s, back when it was still thoroughly feasible. Unfortunately, the people failed to respond. What’s worse, they launched a trend of misinterpretation and misrepresenting the term “Tobet”. Astonishingly enough, the government has chosen this time to take interest in this topic again. Like the proverb goes: the horse has left the barn.

There is no restoring the breed without acceptable breeding material. Enthusiasts work with what they can get, and even enjoy minor success every now and then, but the work is very complicated and making forecasts is hard. Also, these enthusiasts are few and far between, and their resources are extremely limited. The state appears to be showing some initiative, probably allocating some funds, but to tell the truth, this activity of theirs falls outside of what’s actually necessary. The people who are actually capable of doing something for the revival of the breed were on their own – and still are. They still work in their usual tempo – no support, no assistance. As far as I know, these enthusiasts are on the verge of giving up – and some do. All while the state keeps appointing people for the task who are incapable of accomplishing anything. And as for me, I abandoned it all a long time ago and only share my thoughts with those interested when they ask.

Question: Has anyone attempted to collect the genetic material of the Tobet dog to compare it with the DNA of the CAS dog? Your opinion?

Yes, unless I forget, someone at the government voiced an idea like that two or three years ago. We even hosted a delegation of foreign experts from afar, Italy, I think.

In my personal opinion, it is a completely futile and apparently also insanely expensive endeavor lacking any practical purpose.

From the start, there are two issues that reduce the usefulness of such tests to exactly zero. First, we currently have no dogs of the Tobet breed – no one to source the biological material from. Even the somewhat knowledgeable enthusiasts, at best, keep dogs whose genealogy includes aboriginals whose appearance suggests that their distant ancestry included Tobets. “Cousin seven times removed”, but make it twenty. Simply put: there’s no source, no sample for analysis.

The second issue lies in the fact that there are no genetic scientists who know the breed and understand its predicament. As a consequence, when this whole testing thing was announced, many breeders of regular CAS dogs, often of questionable breed quality, hurried to claim that they bred Tobets. Naturally, the geneticists went straight to them to collect and study the biomaterial.

What ensued was that they were sampling CAS dog material to compare it against more of the same CAS material. Foreseeing this situation, I predicted what the results of the study would look like. They’d detect a close relation to the CAS breed and other close breeds, as well as all kinds of impurities introduced by the imported dog breeds. In the end, the results of that study aligned perfectly with my predictions, which I spent all of five minutes to make, several years in advance, and completely free of charge.

Even if we did have actual dogs corresponding to the Tobet breed description available, the study would have still shown a close relation to the CAS breed and its related breeds. This is because the Central Asian Shepherd is a very close relative of the Tobet dog, among others. At the same time, the study would reveal some breed impurities, but possibly not from the imported dogs, or at least to a lesser extent. I am no expert in genetics, but I believe one study is not like the other. It’s even unclear to me what their criteria were – the X chromosome, the Y chromosome, nuclear DNA or something else? The way I understand it, these are all different methods. With a general understanding of the Tobet breed origins, one may claim with confidence that even samples taken from the purest of purebreds would still reveal a clear heterogeneity in ancestors along with possible relations to the various Eurasian dog breeds. What they accomplished by basically sourcing the biomaterial from the CAS dogs twice was to somewhat narrow down the genetic affinity range, limiting it to the breed itself and its closest relatives.

It’s a fact that geneticists are unable to procure the Tobet DNA. But even supposing they succeeded somehow – how would we be able to put it to use?

In selective breeding, dogs are picked based on their phenotype and their traits end up solidified in the genotype. If a dog doesn’t have the right phenotype, then it is no use in selection even if it does have a genetic link to the breed. Am aboriginal dog with the proper phenotype is more likely to have a genuine genetic link to the breed. These are the examples you need to recreate the breed, and you don’t need any genetic studies whatsoever to do so. If a monolithic breed with a stable genotype emerges, then it will arguably make sense to create a genetic passport.

In simpler terms, this whole story with the genetic test did not – and could not – bring any practical benefits whatsoever. Back in my time, I buried a couple of Tobet-type dogs, and I would imagine their remains being somewhat useful for studying. Alas, the land they lay in had since been torn up and built upon. But even if they had been somehow preserved, they wouldn’t have been of any practical use. At best, they’d shed light on one of the aspects or branches of this breed’s genealogical origins. You need statistics to form a more complete understanding, which implies numerous exhumed remains from many regions.

To sum up, I’d like to say it again: all these genetic studies are a pointless and costly undertaking initiated by incompetent people.

Question: is there a kennel somewhere in Kazakhstan or another ex-USSR republic where they spent many years selecting for the Tobet breed?

On a governmental level, no such kennels have ever existed, anywhere. There were two attempts on behalf of affluent private individuals to create such kennels. They sincerely wanted to accomplish something, so they funded the kennels and brought all relatively promising aboriginal dogs there. Ultimately, both have failed. The way I understand it, it was due to incompetence – improper organization, hiring unqualified personnel, perhaps inadequate funding, and so on. As a result, a considerable quantity of promising breed material was simply lost, allowed to fade into oblivion.

Later on, a person named Sultan Ibragimov made a substantial effort to bring together isolated enthusiast breeders and coordinate their work. Financially indisposed despite his full-time employment, he had nonetheless spent many years searching for and recovering aboriginal dogs. He couldn’t afford keeping a whole kennel in his backyard. Because of this, he tried to find and recruit other people for the task, entrusting the dogs he found in their care. This was a difficult process – many people were inexperienced in dog keeping and failed to apply due diligence or realize how expensive it would be.

Most of the dogs Sultan procured were elderly, in poor health, and needed serious veterinary aid. Both Sultan and his newborn community of enthusiasts would often simply lack the time or the means to treat the dogs, take care of them, conduct selection work, and so on. Thus, regretfully, many of these dogs – some of them highly promising as breed specimens – passed on without leaving any offspring.

It should also be pointed out that the breeders who truly want to work towards restoring the Tobet – and these are few and far between – often lack understanding of the breed proper, or lack a coherent vision of it, disagree on what it is, lack organization and a uniform direction. A breed is living matter, and a dog’s life isn’t that long. They end up wasting tons of time bickering among themselves even as the breed essentially vanishes from existence. A small group of enthusiasts led by Sultan continues the work to this day, though, and I would like to wish them the best of success.

I should also mention a single-breed CAS club in Almaty (Alma-Ata), founded and led by Zhakyp Ispolaev. As part of his club’s event schedule, for quite a while now, he’s been holding exhibitions dedicated to the Tobet breed. These are sometimes attended by more or less decent specimens. Right now, Zhakyp Ispolaev has a role of selection and breeding specialist in a government-led program on restoring the breed. He also deserves all the best wishes in this challenging mission.

Question: if a CAS dog is born with lighter-hued brows or a reverse mask on its face and a mane, is it fair to consider this the result of a Tobet gene manifesting itself (as long as the rest of the offspring looks completely different)?

Yes and no. If there is a Tobet or Tobet-type dog among the pup’s closest known ancestors, then such genetic manifestations are to be expected. If not, then they may indicate literally anything. Lightened mask and brows are characteristic of the Tazy hunting dog breed, so it may be their inherited genes, or genes from an Eastern European shepherd, or a German shepherd, and so on. Slightly linger fur around the neck may also be inherited from any number of breeds. One must also consider that, generally speaking, all these traits aren’t atypical of the CAS breed itself. The more generations separate a CAS dog from its Tobet or Tobet-type ancestor, the smaller the odds that this ancient genetic legacy shows up so directly. As multiple generations pass, certain traits get solidified in the genotype. In this case, one needs a more complex approach – consider not only the face and the fur length, but also the quality of the fur, the shape of the head, and so on.

Although, in theory, if you spend many generations selectively breeding dogs with fairly strong Tobet traits – not just those I mentioned above – then the odds are good that you will ultimately end up with something resembling the original breed. Actually, this is what the breed restoration enthusiasts are doing in Kazakhstan these days, with the caveat that they breed aboriginal dogs who possess certain exterior and other features characteristic of the Tobet.

Question: How often do you encounter crossbreeds of the Tibetan Mastiff and Caucasian Shepherds being passed off as Tobet dogs?

If you mean crossbreeding Tibetan dogs with the CAS or aboriginal dogs of Kazakhstan, I haven’t even heard anything about it, let alone seen. Granted, everything is possible nowadays. There’s another thing going with the Caucasian Shepherd. In earlier times, Caucasian Shepherds were abundant in Kazakhstan, and they were quite often crossbred with the Central Asian Shepherds. I believe the same happened with the aboriginal dogs. Much of the time, the results are quite evident. For one thing, the Caucasian Shepherd has a distinct head shape and fur structure. Sometimes you have no idea about the impurity until you learn about the ancestry of the dog – and sometimes, they look very reminiscent of the Tobet. But the issue is, nowadays people often try to pass regular CAS dogs or their crossbred variants for the Tobet. This is a practice that exists.

Question: is there a difference in behavior between Tobet and CAS? I read on the Internet that a true Tobet loves all people and never bites strangers. I mean, it didn’t sound like a guard dog description.

Let’s put it like this: the Tobet and the CAS exhibit similar behavior, with the only difference that the Tobet is less emotional. At their core, both are primarily defenders of livestock from predators – not from humans. Even CAS tend to make less aggressive guards of private households than purpose-breed ones. Their aggression is adequate and highly selective, situation-dependent. In their places of traditional keeping, CAS tend to behave quite properly with strangers. The Tobet is less emotional and, therefore, more reserved in showing aggression. In the end, however, it all boils down to how the dog was raised and the particulars of the situation.

I heard from the elders once that some wolfhounds of the past could dismount the rider from a horse. Normally, the Tobets are phlegmatic, not very noisy, unintrusive and content with simply following the herd paying no attention to strangers – as long as they keep calm. I haven’t seen any Tobets acting aggressive toward humans, but on the other hand, as a city dweller, I haven’t observed them in remote and barely inhabited places. Dogs in their natural habitats may behave differently from areas where they encounter people all the time.

On the other hand, I also head stories about dogs getting quite vicious when our nomadic ancestors practiced their barymta (livestock abduction). But, once again, it was situational. Back then, protection was needed from raiders as well as predators. If a mounted horseman approaches a shepherd, the dogs won’t just attack him at once.

But then came collectivization, sedentary lifestyle, collective farms, state farms etc. Life became peaceful, the banditry and livestock thefts were done with, and there was no longer any need in vicious guard dogs. The most malicious specimens were even shot to death. This might be one of the reasons why the Tobets I met were not aggressive towards humans. Overall, the CAS is also not considered particularly aggressive in this sense, even if you consider dogs born from many generations of urban breeding. Granted, some CAS specimens are fairly aggressive towards humans, and I suppose the same could apply to Tobets, but I haven’t seen many dogs of this breed. Those I’ve seen weren’t like that.

Question: Are there kennels outside of Kazakhstan working on the Tobet breed?

Come on, now. Hardly anyone is working on it in my own country, whoever would bother with Tobet breeding kennels in other republics or countries?

These was a dog keeper from Ukraine in the early ‘90s, can’t remember his name, who claimed he kept some Kazakh dogs. I saw a couple of his dogs firsthand and several more in his photo album – none of them looked remotely like a Tobet.

There’s also a private breeder named Dmitriy R. in Kharkov who takes interest in the breed and is performing selection on Kazakhstan-exported dogs with aboriginal blood in them. He seems to have made some progress. There’s also a breeder in Tyumen who keeps dogs descendant from aboriginal Kazakh breeds. He also has some interesting specimens. That would be all I know, though.

Question: Is there a Tobet to be found anywhere in Kazakhstan?

I suppose that an exemplary specimen of the Tobet may not be encountered at all – whether in our republic or elsewhere. Examples with a varying degree of similarity do crop up from time to time. But they have grown rare, too.

Question: Why were discussions around the Tobet breed reignited again?

The matter is, these dogs existed not long ago at all and were ultimately a part of our cultural heritage, lost as it may be, to my regret. My country only belatedly realized how culturally valuable this breed was to us. Perhaps an idea was born in the minds of the higher-ups somewhere that we should strive to be no worse cynologists than any other nation. That we should make a statement about our national dog breeds, make them one of our country’s iconic attributes. Maybe that’s what all the fuss is coming from. Government officials understand nothing about dog keeping and breeding. They must be thinking that they only need to issue orders, pour money into an obscure black hole, and the breed with magically breed itself back to life. We don’t have many people who understand the breed, and the legal mechanisms devised by the officials don’t even attempt to involve these people in the revival effort.

I personally do not consider myself a big specialist in the breed. I only took a passing interest in it some time ago and collected what information I could find. I wrote clumsy little articles with my friend A.V. Malashevich to attract public attention to the issue when it was still manageable. I have long since retired from that work, but people who refuse to give up hope as they continue trying to bring back the breed still exist in my country. They are few in numbers, and their work has no overlap with whatever the government is trying to do in parallel. If these enthusiasts do manage to reproduce the breed even partially someday, it will be a great success. I keep my fingers crossed for them.

Whichever turn the events take, I must add that, although Tobet-type wolfhounds were widespread in many regions of Central Asia, and provided the bases for what we call the modern-day CAS breed, the Kazakh wolfhounds took an immediate part in this process, too. As history would have it, Kazakhs and Proto-Kazakhs would wander onto Central Asia and the adjacent territories with their livestock and, respectively, dogs. They would settle in for a while, get partially assimilated, and so on. When I was young, larger wolfhounds were often referred to as “kazak-it” (қазақ-ит) in Uzbekistan, which means “Kazakh dog”. In view of this and similar facts, even though aboriginal wolfhounds essentially went extinct in our republic, I can say that they still made their genetic contribution to the modern CAS breed.

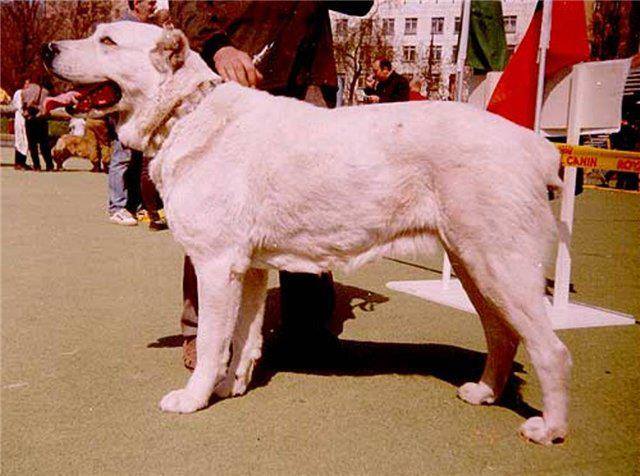

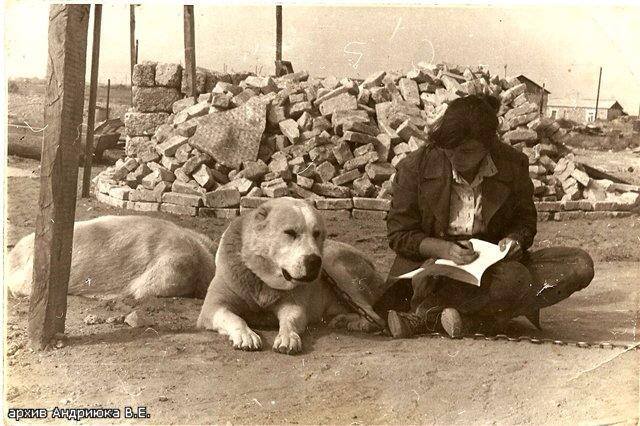

Regarding the photos of the dogs you showed me, I must say they are not Tobets, but Central Asian Shepherds. To give an example, I believe the male named Ezon makes for a fine and vivid specimen of the CAS breed. Still, we must not mislabel him a Tobet under any circumstances.

I hope I could shed at least some light on what the Tobet breed really represents, what its current situation is and how it is interlinked with the CAS breed.

[M1]далее в тексте фамилия несколько раз встречается в написании «Малашевич»; уточнить

[M2]вроде бы чаще встречается такое написание